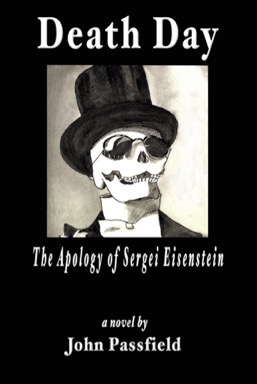

Death Day

The Apology of Sergei Eisenstein

Death Day

The Apology of Sergei Eisenstein

Death Day is available from

AuthorHouse, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble

THE STORY

This novel, Death Day, is an exploration of the plight of the artist in a repressive society, and the strategies that such artists devise in order to ensure their own physical survival and the continuation of their ability to create art under brutal social conditions.

The decade of the 1930s, in Soviet Russia, is a time of public accusations, confessions, convictions and executions of people in all walks of life. For some, the crime is opposition to the rulers of the Communist state; for others – many of them loyal Communists – the crime of which they are accused is simply the independence of their ideas. On March 19, 1937, world-renowned Soviet film-maker, Sergei Eisenstein appears before the All-Union Creative Conference of Workers in Soviet Cinematography, accused of having failed to create films which reflect the social and political orthodoxy of the Stalinist state.

While reeling from the unrelenting barrage of questions, accusations and threats, the mind of Sergei Eisenstein is flooded by the images of his film-making career as he tries to formulate a positive response to his precarious situation. He recalls his triumphant creation of the film, Battleship Potemkin, in the heady post-Revolutionary days when all Communist artists were invited to contribute their ideas and energy to the creation of a bold, new society; his disappointing encounter with the Capitalist alternative, amidst the film-making culture of Hollywood during the Great Depression; and his anguish over how the euphoria of the post-1917 Russian Revolution has been supplanted by a brutally-repressive communist society in which every thought and word is monitored for orthodoxy by the Stalinist Soviet bureaucracy.

As Sergei Eisenstein faces the present-moment crisis of the danger of losing his career, and perhaps his life, he searches for a way out of his dilemma. Realizing that his creativity is his most valuable resource, he reviews two experiences in his past life and career:

– the Best of Times: the making of his film, Battleship Potemkin, which was a time of harmony in his life, his film-making career and his relationship with his society; and

– the Worst of Times: the attempt to make his eventually-aborted film, Que Viva Mexico, when all was disharmony in his life, his career and his society.

Now he faces a situation in which he is at odds with his society, which has become brutally repressive and which seeks to stifle art in the name of propaganda and threatens to end his artistic career.

Aware that he is facing the end of his film-making career – and possibly death – Sergei Eisenstein struggles frantically to find a way out of a dilemma which is faced by all artists in totalitarian states: how to reconcile one’s freedom of imagination and creativity with the conformity to the artistically-stifling orthodoxy which is demanded by the rulers of society? Finally – with thoughts of the cries of the oppressed in all walks of life providing a counter-voice to the presence of the brutal threats of his accusers – Sergei Eisenstein seizes upon an audacious idea, one that he hopes will convince the bureaucrats of Soviet cinema to grant him permission to make just one more film.

But the plan has a double aspect: it is a proposal for a film which he would like to make, but what of the imagery of which this film would be composed? Although the mind of Sergei Eisenstein is aware of his dilemma of the present-moment, he is not necessarily aware of the implications of his own thoughts. All of the action of the novel takes place in the preconscious mind of the main character. The constant bombardment of imagery, from his present, his past and his potential future, is constantly being processed – scrutinized, evaluated and arranged into patterns of imagery – in an attempt to understand what is happening to him and to decide what to do about it. It is fascinating to speculate concerning at what levels of consciousness he is aware of the various aspects of the imagery of his ideas.

The text of the novel is the record of the preconscious thought of Sergei Eisenstein as he stands at the lectern at the Bolshoi Theatre and reviews his entire life and career. Preconscious thought is a combination of layers of thought from the most conscious thought to the most subconscious thought, with many layers of consciousness and subconsciousness operating in concert and in contrast.

I am interested in capturing contemporary life, and the historical roots of contemporary life, in the form of the novel. Contemporary man is bombarded with imagery from more sources than at any time in the past. It is the task of the protagonist of this novel to process this bombardment of images and, by selection and arrangement, to form the images of his experience into patterns which will reveal a meaning which will allow him to live intelligently and compassionately. Form is meaning and I am exploring ways in which the novel can be made to speak in the voices of our time. This novel uses techniques derived from our own contemporary sources of the imagery and information with which we do our thinking – such as film, radio and television, by way of press conferences, interviews and news reports – as a means of creating an exploration of the forces which have contributed to the society in which we all live.

While writing this novel, I kept a planning notebook and a reflective journal. The three companion books – the novel, Death Day; the journal, The Making of Death Day; and the planning notebook, Planning Death Day – are the eleventh installment is a series which traces the making of each novel and the development of my theory of the novel as an art-form.