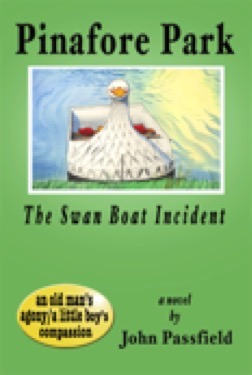

Pinafore Park

The Swan Boat Incident

Pinafore Park

The Swan Boat Incident

PINAFORE PARK is available through the author at

The Story

It is July 6, 1925, in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada. The biggest public event of the year. The whole town gathers in Pinafore Park at a Sunday School picnic, to celebrate the beginning of the summer.

It is one man’s proudest day. He has designed and built a swan boat so the little kids can go out on the water in safety, leaving their parents free to enjoy a day at the park. The day is golden; the feast at noon is a celebration of life. The games are played; the prizes are given. Old men play horseshoes and people sit and talk in the shade while canoes and rowboats join the swan boat out on the pond.

However, unknown to the man who built it, and to everyone else at the picnic, the swan boat is slowly filling up with water. Every turn of the paddle wheel is splashing water into the hull, bringing the laughing children closer and closer to disaster.

Then, suddenly, during the last ride of the day, with the picnic coming to a close, with the swan boat filled to capacity, carrying twenty-one children, two adults and the teen-aged operator, the boat that made the day so special begins to sink, and then rolls over, in full view of hundreds of boaters and near-by picnickers.

The scene is chaotic, as women and children are pulled out of the water and the on-lookers try to determine how many children were on the boat. The lack of accurate information and the initial assumption that all were saved delays rescue efforts. Seven children and one adult drown, and are lost in the murky waters, despite the closeness of so many potential rescuers. The counting of the children reveals the extent of the disaster, and repeated efforts by divers leads to an all-night vigil in the park in search of the bodies. Car headlights play across the scene and bonfires crackle. The shock, the mourning and the attempt to understand the disaster are chronicled in the community’s effort to heal itself.

Five months later, a few days before Christmas, as the community gradually recovers, the story focusses on two sensitive individuals who continue to review the events of the day of the accident, long after the shock has subsided. One rememberer is William Stoner, the builder of the boat, who is drowning emotionally in guilt and isolation from the community. The other rememberer is Billy Townsend, a little boy who almost drowned in the accident, and who becomes aware that the old man is suffering - drowning in his own misery.

Although their paths cross a number of times during the day of the disaster, they do not meet again, face to face, until the last chapter of the story, in which Billy Townsend becomes William Stoner’s rescuer.

The Setting

I grew up in St. Thomas about four blocks from Pinafore Park. At the park, I used to swing on the swings and climb on the monkey-bars while listening to the music from the band shell. I ran three-legged races and ate sandwiches at Sunday School picnics and cheered the local heroes while I watched the inter-county baseball games. I fished and swam in Pinafore Pond and occasionally, I would hear a brief reference to a swan boat that had sank years earlier during a Sunday School picnic.

On rainy days, I would read, in my bedroom on Oak Street, often from an old dictionary, but aside from a booklet about the life of Jumbo, the world’s largest elephant, there was never anything to read about my home town. As I grew up, and became interested in literature, I read stories set in London and Paris, New York and Los Angeles, Moscow and Borneo, Persepolis and Samarkand, but never anything that brought my imagination closer to home. I assumed that these towns had a mythical magic that my birthplace did not, and that my distance from the sources of literature was an unlucky accident of my birth. It is only gradually that I have come to realize that the newspapers of small towns are the great treasure trove of stories from which our future literature can be written, and that writers from Sophocles to Chaucer and from Dickens to Dylan Thomas have realized that a town is only as mythical as its writers perceive it to be.

The Structure

The two main characters, a little boy and an old man – Billy Townsend and William Stoner – remember the events of the day of the picnic while moving through a routine day five months later, in December 1925. Neither is aware of the other’s thoughts or movements on that December day, yet they are both reliving the same central event. They will not meet again until the last chapter.

The two characters are rememberers rather than narrators as they are not consciously telling a story to an audience. The effect, for the reader, is the same as overhearing a person talking on a cell phone. Small mysteries are created which require further and closer reading to solve. The story is revealed at the level of pre-conscious thought; the style is that of conversational speech.

Each chapter has a frame and an inner story. In every chapter except the last one, the story begins and ends with the December day of remembrance, and includes an inner core of memories of the day of the picnic and accident of the previous July.

The memories are the images with which the two main characters are able to come to an understanding of their situations. The images which are not part of the original story – such as oak trees and black swans – are placed subconsciously in the order in which they can best reveal the meaning that will lead to compassion for Billy Townsend and healing for William Stoner.

Each rememberer goes through the December day chronologically: Billy Townsend goes through the last day of school before the Christmas holidays, and William Stoner goes uptown to do some Christmas shopping and then returns home. Similarly, each rememberer recalls the events of the July picnic in chronological order.

Although the two are unaware of each others’ thoughts, the alternating chapters form one story of two minds who share a problem and a solution.

The Newspaper Articles

The two protagonists, the young Billy Townsend and the old man, William Stoner have kept a scrapbook of newspaper articles featuring account of the disaster. Each has read them many times. The identical contents of the scrapbooks form a backbone of historical narrative which connects the memories of the two characters. The content of the articles is part of the subconsciously-shared memory of both Billy Townsend and William Stoner.

The newspaper articles also carry the main thrust of the historical narrative and tell the story of the way in which a community suffers a shocking disaster and slowly recovers from it. The fictional thoughts of the two main characters show the personal story behind the public event, as the disaster continues to affect two sensitive people who participated in the accident.

The newspaper articles are relentless, The reader experiences both the present enjoyment and the future devastation of the event at the same time; the cheerful triviality of the characters’ everyday lives and the optimism of their assumptions is constantly being undercut by the reminders of the grim outcome of that day. However, I would hope that the reader becomes engaged in the same struggle as the two main characters, which is to achieve a sense of balance: a realization that the day in the park was a celebration of life as much as a loss of life, and that the value of the joys of life are equal to – even if they can’t overcome – the inevitable ending of all of life in death.

Complexity and Simplicity

As a writer, I am interested in exploring the many variations of narrative technique and the possibilities of the poetic novel. My aim has been to write a novel which is extremely simple on the surface, and yet very complex and subtle underneath. An accident has happened: an old man feels guilty and seeks understanding; a little boy feels compassion and tries to help. No matter what the complexity of the technique or imagery, every page reminds the reader of the central fact that is being examined by both characters: a swan boat has rolled over at a Sunday School picnic and seven children have drowned. That is about as simple and clear a central image as a story could want. All of the rest is an exploration of the implications of that fact.

PINAFORE PARK is available through the author at